As Toronto’s skyline continues its vertical ascent, a new type of skyscraper is reshaping the conversation around how we live, build, and grow.

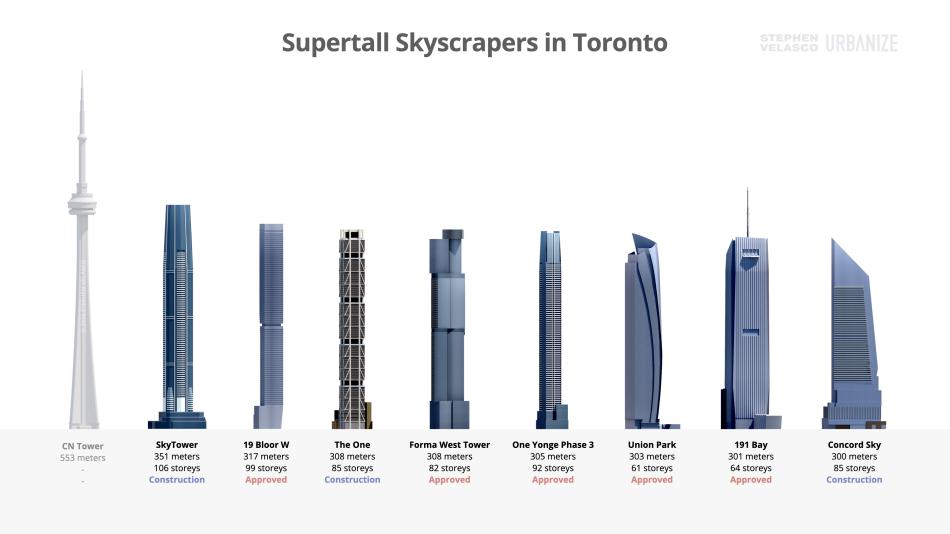

According to the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH), a supertall skyscraper is any building 300 metres (984 feet) or taller. While none currently exist in Canada, three are currently under construction in Toronto: SkyTower at Pinnacle One Yonge (351 metres / 106 storeys), One Bloor West (308 metres / 85 storeys), and Concord Sky (300 metres / 85 storeys), with five more currently approved.

These ambitious projects mark Toronto’s entry into a global league of high-density urban centres tackling complex challenges around housing, livability, and intensification.

Renderings of three of supertall skyscrapers currently under construction in Toronto. From left to right: SkyTower at Pinnacle One Yonge, One Bloor West, and Concord Sky.

Renderings of three of supertall skyscrapers currently under construction in Toronto. From left to right: SkyTower at Pinnacle One Yonge, One Bloor West, and Concord Sky.

At the centre of this vertical shift is Mansoor Kazerouni, Global Director of Architecture and Urbanism at Arcadis — the same architectural firm behind the design of 19 Bloor West, an approved 99 storey supertall mixed-use residential tower near the corner of Yonge and Bloor. With more than three decades of international experience across North America, the UK, India, and the UAE, Kazerouni has led transformative projects ranging from master plans and mixed-use districts to tall towers and civic landmarks — all shaped by a strong focus on sustainable design and innovative urban strategies.

In this exclusive Q&A with Urbanize Toronto, Kazerouni provides insight into the development and complexities of supertall skyscrapers, and what they can offer for the future of growing cities like Toronto.

Q: When designing a supertall residential tower, how does your approach differ from a conventional high-rise beyond just height?

A: “We’re designing with very particular parameters in mind, and above 70 storeys, there’s quite a change in complexity.

As an example, we deploy damping technology — either a sloshing damper, a tuned mass damper, or other devices — that reduces the acceleration so that you don’t feel uncomfortable when you're on the building’s top floors. This technology has implications in terms of space and structural requirements, construction duration, and cost. There are also other requirements that come into play, whether it is how we align the structural system with the core, the stiffness of the core elements, or the way we deploy mechanical systems — all of these things may not have been necessitated at 50 storeys.

A lot of it is about wind resistance at those heights because the more surface area you present for the building to resist the wind, the more the building will move. We've also seen towers around the world with big holes in them, allowing the wind to pass through to reduce or minimize that resistance. All kinds of design considerations come into play with supertalls that you don't necessarily encounter at lower heights.”

Q: What zoning or regulatory hurdles have you encountered with supertall proposals —Why is Toronto seeing the emergence of supertalls now?

A: “I don't think the rule book changes. You have more hoops to jump through and more hurdles to cross, but there is greater scrutiny of these projects from the point of view of their performance, and their built-form impact on the environment.

I think with the intensification that Toronto has experienced, supertalls have become a valuable tool in the toolkit for addressing housing needs. We’re increasingly seeing supertalls proposed in close proximity to higher order transit and in urban environments where it makes the most sense to locate these kinds of towers.”

Height comparison of supertall skyscrapers planned or under construction in Toronto.Image Credit: Stephen Velasco

Height comparison of supertall skyscrapers planned or under construction in Toronto.Image Credit: Stephen Velasco

Q: Is there a tipping point where super tall residential towers become unfeasible — what factors typically determine that threshold?

A: “It’s always a balance. As the structural components take over, you hit a point of diminishing returns. There are towers we've designed to a certain height and then cut down because it didn't make sense anymore to go that much taller.

Some of it may be driven by cost, functionality, and programmatically, where you start to worry about market absorption and elevator performance (the number of units or people per elevator). If you hit a point where, by adding a floor, you're adding another elevator, but you're just adding 20 units — you’re probably going to cut it back, right? You're losing a lot of saleable area with the elevator shaft penetrating the floor plate since it impacts every single floor plate up the tower.

There are also issues around stack effect, or wind rushing up the building every time someone opens the front door on the ground floor. The pressure created can be so high that you can't even open the door to your unit. So, we've got to anticipate these things and to design for them, ensuring that we have the right kind of mitigation in place to make them as livable and comfortable as a 20-, 30-, 50-storey tower.

The cost-benefit program analysis constantly happens throughout the design process as we review the towers and evaluate their overall feasibility.”

Q: Contrasting New York’s Billionaire’s Row and Toronto’s approach to supertall residential towers — how do you see developers balancing the demand for affordability, livability, and density?

“If you look at the supertall residential towers along 57th Street in New York City, they are awe-inspiring… there's a reason that that collection of towers is now referred to as Billionaire's Row. That's the market in a city like New York, which is a global destination that attracts some of the wealthiest in the world who want to have either a permanent or a semi-permanent residence there. So, they tend toward larger units in many of those towers.

Toronto hasn't tended that way, but I do think that in these tall towers, there is an opportunity for segmentation, where you could exponentially increase the size of the units as you go up — but you've got to understand the target audience, and cater to that, even from an affordability perspective, which is why we see up to 1,000+ units in a tower in Toronto. We've got to ensure that we have elevated levels of service in these towers when we design to those heights with that many units.”

Several super slender supertall residential skyscrapers now rise above 57th Street in New York City - also referred to as Billionaire's Row.Image Credit: Stephen Velasco

Q: Tall buildings often attract criticism — from concerns around affordability to shadowing. How do you respond to these concerns, and what benefits or opportunities do these developments unlock?

A: “I can't think of a single project we've done at any height in any neighbourhood in the GTA where we've been told: ‘This is exactly what we need!’ by the community.

I've all too often heard, ‘It's a beautiful building, it's a beautiful design, just find another site for it, not in this neighbourhood.’. I think much of the community — the neighbourhoods that we design and build in — acknowledge and recognize the need for additional housing, for the city to grow upward in a sense. But there's this fear around change and the impacts that it's going to have, which is understandable.

We work with the communities that we serve and look for the opportunities that can come out of it — whether it's elevated public realms, additional parks and open spaces, schools, community centres, or better access to some other social infrastructure amenity that goes beyond benefiting just the development, but the community at large. So, I think it's part of the inevitability of the evolution of our cities, notwithstanding some of the challenges and criticisms that we encounter.

From a design perspective, I think it matters. Whether it's the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, or the Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur, they somehow become closely associated with the identity of these cities. I think as architects and urbanists, we have a design responsibility.

Is it a good thing? Is it a bad thing? That's highly subjective. But for those of us that love cities, I think they're a beautiful thing.”

Q: As Toronto continues to grow, how do you see the role of supertall towers shaping its future?

A: “300 metres is the entry point. As Toronto evolves, it’s joining the ranks of highly developed and denser cities, where it's going to be inevitable that we'll see more of these buildings.

While we should heighten the effort in mitigating the impact that these buildings have and collectively bring a responsible lens to them, I do think that we should facilitate them where they are appropriate because they will become beacons for our city, just as cathedrals and clock towers became visual identifiers during other times in history. And so, I think skyscrapers are here to stay. They are very much a part of the built form of cities of the future.

I used to say: ‘You've got to have the ambition to do a 100-storey tower’.

We’re at 99 storeys with 19 Bloor — but it's great to see that our cities have evolved to that height, and I'm looking forward to working on more.”

About Mansoor Kazerouni

Mansoor Kazerouni is the Global Director of Architecture and Urbanism at Arcadis, recently ranked the second-largest architectural practice in the world by WA100. With over 30 years of experience, he has led diverse projects across North America, the UK, India, and the U.A.E., including master planning, residential, commercial, hotel, and institutional developments, with a strong focus on sustainable design and innovative urban strategies.

A licensed architect and member of the Ontario Association of Architects (OAA) and the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (RAIC), Mansoor is a respected thought leader who serves as an expert witness in development-related proceedings. He is also a passionate mentor and frequently lectures at universities, conferences, and industry panels.